Between 1993 and 2001, bodies with their heads ripped off began washing up on shore.

A killer mystery

Between 1993 and 2001—on a tiny speck of an island in the North Atlantic—a strange and grisly phenomenon began to become commonplace. Mutilated bodies—many with their heads ripped off—began washing up on shore.

During that time, researchers examined 4906 seal corpses found on Sable Island. Five seal species—grey, harp, harbour, hooded, and ringed—were involved. All bore wounds resembling those inflicted by shark attacks. The nature of the wounds pointed to two or more shark species as the culprits.

Which way to the beach?

Sable Island is a crescent-shaped sandbar—basically a giant beach—located at the outer edge of North America’s eastern continental shelf, approximately 160 km southeast of mainland Nova Scotia, Canada. The island—famous for its population of wild horses—is a breeding and pupping ground for harbour seals, and is now home to the world’s largest grey seal breeding colony. Prior to the early 1990s, shark predation on seals near Sable Island was sporadic. But a sharp increase in attacks was noticed in January 1993.

Wounds on seal carcasses found in the summer had the trademarks of traditional slashing injuries, and from tooth marks found on the bones, a usual suspect in the predation of marine mammals emerged: the Great White Shark.

It’s no surprise that Great Whites inhabit these waters during the summer and fall months—especially large sharks—as the water temperature at this time is well within their warm-bodied range, and continues to get warmer each year. However, that only accounted for 2% of the attacks. The other 98% occurred in January-February, when water temperatures are way too cold for Great Whites.

Do the twist

Another oddity about the winter attacks was that the bodies bore strange corkscrew-like wounds, unlike any found on marine mammals killed by sharks in other parts of the world. The extremely unusual, long clean-edged corkscrew wounds suggested a different cause, such as manmade hazards, ice, or other predators like Killer Whales (Orcas).

Each theory was ruled out because:

- The wounds were markedly different from those seen on manatees injured by ship propellers, and evidence that some kills had occurred close to the beach further ruled out propellers since Sable’s shoreline is not accessible to ships.

- The wounds also bore no similarity to entanglement injuries caused by net, rope or strapping, and because access to Sable Island is restricted and activities monitored, it was improbable that the wounds were deliberately inflicted by humans.

- Pack ice does not normally occur within 200 km of Sable Island.

- Killer Whales are uncommon in that area, and the clean-edged wounds were not consistent with the dentition or feeding behaviour of Orcas.

No jacket required

All corkscrew wounds were so clean-edged that they appeared to have been made with a sharp instrument. The wound typically penetrated hide and blubber, but did not cut into muscle tissue. Although the bones of face and jaws were sometimes fractured, other skeletal material, trachea, and organs were most often intact (except for damage caused by scavenging gulls).

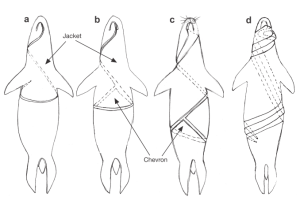

In over half of the examined complete corpses, the corkscrew wound was almost identical. A long, single tear line with no tissue missing. The remaining complete corpses bore wounds comprised of two or more parallel tears, sometimes with a small patch or strip of tissue missing from the face or neck. Incomplete corpses missing tissue ranged from strips of hide and blubber, to the entire front half or front three-quarters of the body.

Most often the missing tissue was a jacket, the section of hide and blubber from the front half of the body, with both front flippers, and usually scapulae, attached.

Cast a wide net

Photographs and diagrams of the corkscrew wounds were sent to researchers studying pinnipeds and sharks all over the world. Reports came in suggesting that similar injuries had been seen on seals in the same time period along the North Sea coastline and in Norway. In those cases, the suspect was the little-known Greenland Shark.

Once thought to be mainly a slow moving, scavenging Arctic or deep-water shark, recent research has proven the Greenland Shark lives much further south than ever thought, and that it comes into shallow water to feed.

It is likely that Greenland Shark behaviour near Sable Island is not unique, and the species similarly preys on seals in other regions where it coexists with pinnipeds. However the scarcity of reports suggests that:

- Such predation has not occurred until recently in other regions.

- Such predation has occurred, but the corpses have not been observed or reported because the breeding colonies may be away from land and on ice making corpses unlikely to wash ashore.

- These wounds have been seen in the past, but the damage has been attributed to ships’ propellers, rafting ice or deliberate mutilation.

Full set of utensils

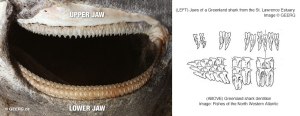

The teeth in Greenland Sharks’ upper and lower jaws are very different. The upper teeth are small and thorn-like. The lower teeth are about half as broad as high, overlapping and forming a continuous saw-like or bread knife-like cutting edge.

The upper teeth, which are not cutting teeth, help to hold and manipulate the prey. Greenland Sharks’ mouths are also modified for suction feeding, and it is capable of using a wide variety of food capture strategies on a single food type. The prey may be captured by suction, while the upper teeth hold the prey in place during a lateral head shaking that allow the lower teeth to make a sharp cut.

The Greenland Shark grasps the live seal front first, and the lower teeth cut into the hide. The hide tissue with blubber attached is held and pulled by both teeth and suction. The seal’s struggles—along with head shaking by the shark—tears the hide, and the jacket is pulled free of the carcass.

Opportunity knocks

The Greenland shark is a generalist predator, with prey including fish, other sharks and rays, seabirds, squids, crabs, large mollusks and jellyfish. One specimen was found with an entire reindeer in its stomach (minus the antlers).

Also an opportunist, Greenland sharks will feed on carrion, and were often seen gathering in shallow waters around whaling stations to take advantage of offal and camp garbage.

The remains of harbour, ringed, harp and hooded seals have been found in large Greenland sharks from many locations, but it wasn’t until 2007—when freshly killed pinnipeds were found in their stomach contents—that these cold-water sharks were believed to actively hunt live seals.

Chew the fat

In more than half of the corpses examined, very little to no tissue was missing, suggesting that the shark did not feed on the corpse. Why would a Greenland Shark tear off the jacket and leave the rest of the carcass? It might not be a feeding event at all, or a failed feeding attempt. However, it’s more likely that the sharks are selectively feeding on the most energy-rich portion of the seal. The energy content of blubber is roughly twice that of muscle tissue. And even on carcasses where tissue was missing, it was a section of hide with the blubber layer attached.

Something in my eye

Recent research on the Greenland Shark—along with dives with the animal—has revealed a strange relationship the shark has with another creature. A small crustacean—called a Copepod—is usually attached to the sharks’ eyes.

Divers have noticed that almost every Greenland Shark has these Copepods attached to their eyes by tiny hooks. It’s unsure if this strange relationship has any benefits for the shark, but the Copepods cause lesions in the eye to the point where it impairs the sharks’ vision. Most are probably approaching blindness in the way that the eye no longer functions as an image-forming camera.

Even if this shark came into shallow water, it stands to reason that it wouldn’t be able to locate seals, let alone kill them. Being a nearly blind scavenger, it could only feed on the seals if they were wounded or weakened.

But the Greenland Shark has an ace up its sleeve. Perhaps as an adaptive response to the Copepods, its nostrils are huge, and the nerves from the olfactory are thicker than the nerves from its eyes, meaning more information is coming in from the nose.

Caught napping

It still begs the question. How could a slow-moving, nearly blind Greenland Shark chase down a fast, alert seal unless it was already vulnerable?

Seals sleep underwater at a variety of different depths—depending on the species—and they are capable of remaining completely still at any given depth. Divers have swum up to sleeping harbour seals and tapped them to wake them up. In low visibility, it seems the Greenland Shark uses its sense of smell to track down sleeping seals, and then uses other senses to pinpoint the exact target for an attack.

Live streaming evolution

Are we witnessing the development of a unique hunting strategy that has been just discovered by the Greenland Shark, similar to that of killer whales in Patagonia that have learned to storm the beaches to catch seals? Perhaps. Regardless, the carnage continues on Sable Island, as this fascinating detective story underscores the untold mysteries of nature.

living on cape breton,for some years now seals have washed up headless,we blame it on ice packs ,are we wron or is this shark hunting close to our beaches

Hi Alan,

I think shark predation is happening along the coastline of Cape Breton, it’s just a matter of which species is doing the hunting. In the winter/spring months, it would almost positively be Greenland sharks. Ice breakup undoubtedly causes some injuries to seals, but if the damage follows a pattern of decapitation and corkscrew-type wounds, I would put my money on Greenland sharks. Once summer hits, predation by white, mako, blue and porbeagle sharks becomes more common.

Thanks for commenting,

Joe

Pingback: The Curious Case of the Sable Island Seal Killer – What !

Pingback: The Curious Case of the Sable Island Seal Killer - Same Crap, Different Day

Pingback: The Curious Case of the Sable Island Seal Killer